When street preacher meets multi-watt speaker meets city bylaw…

You get some interesting discussions on Charter law.

Last month, a Court of Queen’s Bench judge reversed a trial judge’s earlier decision that had sided with Art Pawlowski’s argument that cracking down on his speaker-amplified preaching violated his rights.

Bylaw tickets the preacher faces: $100. Cost the city’s spent on the legal battle: $65,000. And that could rise, since Pawlowksi plans to appeal.

This week, University of Calgary consitutional law expert Jennifer Koshan weighed in on the wonderful ABLAWG:

As noted, the City had conceded that this bylaw violated Pawlowski’s freedom of expression, and (QB) Justice Hall noted that he agreed with (trial) Judge Fradsham’s holding that the ban on sound amplification infringed s. 2(b) of the Charter. Thus the City was obligated to justify this violation under s.1 of the Charter. Was there also a violation of freedom of religion for it to justify?

Unlike Judge Fradsham, Justice Hall answered this question in the negative. He stated the following test from Alberta v. Hutterian Brethren of Wilson Colony, 2009 SCC 37, [2009] 2 S.C.R. 567: “an infringement of s. 2(a) of the Charter will be made out where the claimant sincerely believes in a belief or practice that has a nexus with religion and where the impugned measure interferes with the claimant’s ability to act in accordance with his or her religious beliefs in a manner that is more than trivial or insubstantial”, and noted that for a violation to be more than trivial or insubstantial, “claimants need to show that their religious beliefs or conduct might reasonably or actually be threatened” (at para. 79).

Applying this test, Justice Hall found that on a subjective basis, Pawlowski sincerely believed that his street preaching was required by his religious beliefs and that there was a nexus between the use of a sound amplification system and his beliefs. However, the City’s ban on amplification systems was seen as a trivial and insubstantial breach of freedom of religion. Citing Hutterian Brethren, Justice Hall noted that “a degree of deference is appropriate” (at para. 88). The ban on amplification did not threaten Pawlowski’s religious beliefs or impair his ability to preach to the homeless. Although amplification may have made his preaching more effective in some circumstances, the ban did not meet the threshold for a violation of s. 2(a) of the Charter.

….

Although I believe that Justice Hall came to the right conclusion on many of the issues in this appeal, his reasons seem unclear, inconsistent, potentially misleading, or lacking in sufficient detail or appropriate focus with respect to some of the issues.

….

For the most part Justice Hall’s analysis of freedom of religion is beyond challenge, although as noted above, he did not fully engage with Judge Fradsham’s finding that the City’s violation of s. 2(a) of the Charter was more than trivial or insubstantial. More seriously, Justice Hall stated in his reasons on freedom of religion that “a degree of deference is appropriate” (at para. 88), and attributed this statement to Chief Justice McLachlin in Hutterian Brethren. It must be noted, however, that the discussion of deference in Hutterian Brethren related to the Court’s approach under s.1 of the Charter. There is no authority which states that deference should be provided to government at the stage of interpreting constitutionally guaranteed rights and freedoms, and to the extent that Justice Hall’s decision suggests this approach, it is incorrect.

Street Preaching and the Charter: The City of Calgary’s Appeal in Pawlowski

Written by: Jennifer Koshan

Artur Pawlowski, Calgary’s self-professed street preacher, was acquitted of a number of provincial and by-law charges related to his preaching and other activities in December 2009. Judge Allan Fradsham of the Alberta Provincial Court found that the charges violated several of Pawlowski’s Charter rights, and could not be justified under s. 1 of the Charter (2009 ABPC 362). I argued that Justice Fradsham’s ruling may have been overly expansive in its approach to the Charter (see here). The City appealed the ruling in relation to the bylaw charges, and had some success at the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench. However, the decision of Justice R.J. Hall on appeal raises some analytical questions that I will discuss towards the end of this post.

The Charges

The two bylaws which Judge Fradsham found unconstitutional read as follows:

Parks and Pathways Bylaw, City of Calgary Bylaw No. 20M2003

21. No Person, while in a Park, shall …

(e) operate an amplification system

… except in an area where such activity is specifically allowed by the Director. …

Street Bylaw, City of Calgary Bylaw No. 20M88

17(1) Except to the extent specified in and subject to the conditions of a permit signed by or on behalf of the Traffic Engineer, no person shall:

(a) place, dispose, direct or allow to be placed, directed, or disposed, any Material belonging to that person or over which that person exercises control, on any portion of a Street; …

In s.2(16) of the Street Bylaw, “material” is defined to mean “any object or article, animal waste, ashes, building waste, dry refuse, garbage, industrial chemical waste, refuse and yard waste as defined in The Waste Bylaw, and includes sand, gravel, earth and building products.” Section 2(21) defines “street” to include a sidewalk.

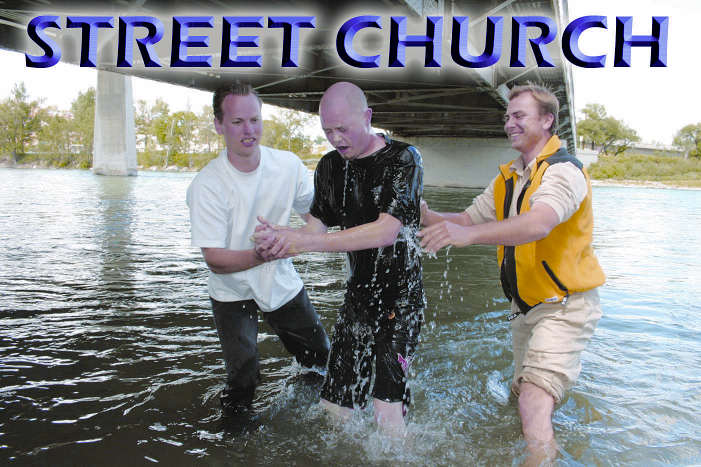

Pawlowski had been charged with numerous infractions under each bylaw arising from activities that took place in April, May and June of 2007. According to an agreed statement of facts, Pawlowski admitted to using a sound amplification system without a permit in Triangle Park in downtown Calgary on two occasions, and to placing materials (sound speakers, signs, tables, banners, boxes full of food, drinks and DVDs, and a large wooden cross) on City sidewalks without a permit (para. 7). Pawlowski testified that these activities were part of his work with the Street Church, activities which included distributing food and literature, praying for people and preaching the gospel (para. 10). He further testified that he believed it was necessary to use sound amplification in Triangle Park to reach a larger audience and to protect himself from drug dealers (para. 15), and noted that “Jesus himself used amplification” (at para. 13). As for the materials placed on City sidewalks, these were associated with the Street Church’s mission to assist the poor and take the gospel to the people (para. 15). Pawlowski initially received some support from the City, however after numerous noise complaints and the failure to reach an agreement regarding some form of accommodation, the City refused to grant Pawlowski permits for his activities. Pawlowski was also under order of the Court of Queen’s Bench not to use amplified sound and had been found in contempt of court for breaching this order (see Pawlowski v. Calgary (City), 2008 ABQB 267 and my post on this decision). It was under these circumstances that the City laid several charges against Pawlowski for bylaw infractions.

Trial Judgment

At trial, Judge Fradsham found that the ban on the use of an amplification system in City parks in the Parks and Pathways Bylaw was not vague or overbroad, however it did violate Pawlowski’s freedom of religion under s.2(a) of the Charter and his freedom of expression under s.2(b) of the Charter. Neither violation was found to be justifiable by the City under s.1 of the Charter as a reasonable limit on Pawlowski’s freedoms. Judge Fradsham further found that the ban on placing materials on City streets in the Street Bylaw was vague and overbroad, contrary to s. 7 of the Charter. This bylaw was also found to have the effect of violating Pawlowski’s freedom of religion and expression, and neither violation could be justified under s.1 of the Charter. Both bylaws were held to be of no force or effect in relation to Pawlowski and he was acquitted of the associated charges. Judge Fradsham did not accept Pawlowski’s argument that the City had engaged in abuse of power in its refusals to accept permit applications from Pawlowski.

The City’s Appeal

The City’s only concession on appeal was that the Parks and Pathways Bylaw violated Pawlowski’s freedom of expression. It argued that that violation could be justified under s.1 of the Charter, and that the ban on sound amplification did not violate Pawlowski’s freedom of religion. As for the Street Bylaw, the City argued that it did not violate Pawlowski’s freedom of expression or religion, and that any such violations were justified under s.1 of the Charter. The City also argued that neither bylaw was vague or overbroad. Pawlowski of course took the opposite position on each of these issues. He did not cross-appeal the dismissal of his abuse of power claim.

Justice Hall began by noting that the proper standard of review was that of correctness for questions of law, and that of palpable and overriding error for questions of fact.

He first considered arguments related to the vagueness and overbreadth of the Street Bylaw. Justice Hall noted a recent relevant case out of the British Columbia Court of Appeal, Vancouver (City) v. Zhang, 2010 BCCA 450, in which a similar bylaw had been found to meet constitutional standards regarding vagueness and overbreadth. However, the bylaw at issue in Zhang had some key differences with s.17(1) of the Street Bylaw, as it focused on objects placed on streets that created “an obstruction to the free use of such street, or which may encroach thereon…” (Street and Traffic Bylaw, Revised Bylaw No. 2849, cited in Pawlowski at para.57). The City of Calgary argued that s.17(1) of its Street Bylaw should be read as if it applied only to materials creating obstructions on the streets – the “reading in” argument. The City also relied on the principle of ejusdem generis to argue that “material” as defined in s. 2(16) of the Street Bylaw “constitutes an identifiable class comprised of objects that do not have any place or purpose on a public street and have in common that they frustrate the purpose of a municipal street, which is to provide free and navigable passage for pedestrians and other users of that street” (at para. 59) – essentially a “reading out” argument.

Justice Hall rejected both of the City’s interpretive arguments. As for reading in the aspect of obstruction, he noted that the City could have used this explicit language in the bylaw if its intent was to prohibit obstructions (at para. 63). Further, relying on National Bank of Greece (Canada) v. Katsikonouris, [1990] 2 S.C.R. 1029 at 1040, Justice Hall held that ejusdem generis only applies when a list of specific terms is followed by a general term, and not vice versa. Because the general term “any object or article” precedes the specific terms referencing waste and refuse in s. 2(16) of the Street Bylaw, ejusdem generis was inapplicable to the case at hand (at para. 62). The words “any object or article” should not be read out or interpreted in light of the more specific terms in the section, and that left a prohibition which was said to be “alarming” in its overbreadth. Referring to many of the same examples used by Judge Fradsham, Justice Hall noted that the ban on the placement of objects and articles on City streets could apply to shoes, baby carriages, briefcases, and vehicles (at para. 67). He accepted Judge Fradsham’s analysis that s.17(1) of the Street Bylaw, read in light of the definition in s.2(16), was vague and overbroad, and dismissed the appeal related to this bylaw. There was therefore no need to consider whether the Street Bylaw unjustifiably violated Pawlowski’s freedom of religion or expression.

Justice Hall also considered a vagueness / overbreadth argument in relation to s. 21(e) of the Parks and Pathways Bylaw. “Amplification system” was not defined in the bylaw, and Pawlowski argued that “amplification” could refer to light as well as sound, and could result in bans on iPods, cell phones and flashlights.

Justice Hall decided that for this bylaw, the modern approach to statutory interpretation should be taken, as established in Rizzo & Rizzo Shoes Ltd. (Re), [1998] 1 S.C.R. 27 at para. 21: “today there is only one principle or approach, namely, the words of an Act are to be read in their entire context and in their grammatical and ordinary sense harmoniously with the scheme of the Act, the object of the Act, and the intention of Parliament”.

Applying this approach, Justice Hall determined that the Parks and Pathways Bylaw was intended to protect public safety, accessibility, aesthetics and the environment in relation to City parks. More specifically, s. 21(e) was intended to limit sound amplification systems, and should not be read to include iPods or cell phones because these items do not “affect the safety, accessibility and enjoyment of the parks by the general public”. Rather, s. 21(e) should be interpreted to “prohibit noise amplified to such an extent as to interfere with the enjoyment of the park by other users” (at para. 75). He noted that Montréal (City) v. 2952-1366 Québec Inc., 2005 SCC 62, [2005] 3 S.C.R. 141, which had not been cited in Judge Fradsham’s decision, was persuasive (at para. 75). Section 21(e) of the Parks and Pathways Bylaw was not vague or overbroad.

This left the freedom of religion and expression arguments in relation to the Parks and Pathways Bylaw to consider. As noted, the City had conceded that this bylaw violated Pawlowski’s freedom of expression, and Justice Hall noted that he agreed with Judge Fradsham’s holding that the ban on sound amplification infringed s. 2(b) of the Charter. Thus the City was obligated to justify this violation under s.1 of the Charter. Was there also a violation of freedom of religion for it to justify?

Unlike Judge Fradsham, Justice Hall answered this question in the negative. He stated the following test from Alberta v. Hutterian Brethren of Wilson Colony, 2009 SCC 37, [2009] 2 S.C.R. 567: “an infringement of s. 2(a) of the Charter will be made out where the claimant sincerely believes in a belief or practice that has a nexus with religion and where the impugned measure interferes with the claimant’s ability to act in accordance with his or her religious beliefs in a manner that is more than trivial or insubstantial”, and noted that for a violation to be more than trivial or insubstantial, “claimants need to show that their religious beliefs or conduct might reasonably or actually be threatened” (at para. 79).

Applying this test, Justice Hall found that on a subjective basis, Pawlowski sincerely believed that his street preaching was required by his religious beliefs and that there was a nexus between the use of a sound amplification system and his beliefs. However, the City’s ban on amplification systems was seen as a trivial and insubstantial breach of freedom of religion. Citing Hutterian Brethren, Justice Hall noted that “a degree of deference is appropriate” (at para. 88). The ban on amplification did not threaten Pawlowski’s religious beliefs or impair his ability to preach to the homeless. Although amplification may have made his preaching more effective in some circumstances, the ban did not meet the threshold for a violation of s. 2(a) of the Charter. In reaching this conclusion, Justice Hall did not refer specifically to Judge Fradsham’s findings that the requirement to obtain a permit to use amplified sound and the act of ticketing Pawlowski while saying grace were more than trivial or insubstantial breaches of freedom of religion (at para. 239).

The final issue was whether, as a violation of freedom of expression, the ban on amplification systems in City parks could be justified as a reasonable limit under s.1 of the Charter. Applying the test from R. v. Oakes, [1986] 1 S.C.R. 103, Justice Hall easily found that s. 21(e) of the Parks and Pathways Bylaw had a pressing and substantial objective – “to ensure that City parks and pathways remain safe and accessible for enjoyment of all Calgarians” (at para. 94). Further, controlling noise in parks through a ban on amplification systems was found to be “certainly rationally connected” to the objective of ensuring accessibility of parks by the public (at para. 95). The final two stages of the Oakes test were somewhat more contentious.

On the question of whether the ban on amplification systems minimally impaired Pawlowski’s freedom of religion, the Montréal (City) case was seen as significant once again by Justice Hall. That case involved a municipal ban on noises produced by sound equipment that could be heard outside. According to the passage from Montréal (City) cited by Justice Hall at para. 96, the following factors are relevant at the minimal impairment stage: in cases of competing interests on social issues, governments must be given some latitude in deciding how to balance interests; noise may be difficult to regulate by degree of loudness; and governments may have an interest in eliminating certain kinds of noise, i.e. those produced by sound equipment. Justice Hall agreed with the reasoning in that case, finding that “[t]he ban on amplification systems in parks is a practical method of controlling noise in the use of public parks; it is probably the most practical and effective way of doing so. … It does not curtail public discourse. It simply limits its volume.” (at para. 97). The ban was found to be minimally impairing of Pawlowski’s s. 2(b) rights.

The final question under s.1 was whether the salutary effects of the bylaw outweighed its negative effects on Pawlowski’s freedom of expression. Here too Justice Hall relied on the Montréal (City) case. He rejected the argument accepted at trial that Triangle Park had become a place where the usual functions of parks had been disrupted by homelessness, drug trafficking and criminal activities, such that Pawlowski’s use of amplified sound “was not incompatible with that corrupted usage.” (at para. 100). Justice Hall noted that even though he accepted the facts concerning Triangle Park, Calgary citizens had still complained about the amplified noise in the park. As in the Montréal (City) case, the fact that the noise occurred downtown “does not, however, mean that its residents must necessarily be subjected to abuses of the enjoyment of their environment.” (at para. 102). Overall, the benefits of s. 21(e) of the Parks and Pathways Bylaw were seen to outweigh the bylaw’s prejudicial effects on Pawlowski.

The City’s appeal related to s. 21(e) of the Parks and Pathways Bylaw was therefore allowed, and Pawlowski was found guilty of two incidents of violating the bylaw.

Commentary

Although I believe that Justice Hall came to the right conclusion on many of the issues in this appeal, his reasons seem unclear, inconsistent, potentially misleading, or lacking in sufficient detail or appropriate focus with respect to some of the issues.

First, the legal basis for Justice Hall’s decision that the Street Bylaw was vague or overbroad was not made explicit. At trial, Judge Fradsham based this finding on s.7 of the Charter, which guarantees “the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.” Judge Fradsham found that the ban on material on the street was vague and overbroad, and thus contrary to the principles of fundamental justice. Justice Hall indicated (at para. 68) that he accepted Judge Fradsham’s analysis on vagueness and overbreadth. However, he did not cite s.7 of the Charter in his reasons, indicating that perhaps his decision on vagueness and overbreadth was based on the validity of the bylaw under the requirements of municipal law (see e.g. Montréal (City), above). There is language at paragraphs 55 and 76 to support this interpretation, but given the basis of Judge Fradsham’s decision this should have been made clearer.

A second difficulty with Justice Hall’s reasons on vagueness and overbreadth is the inconsistent approach to statutory interpretation he employed for the two bylaws. In the case of the Street Bylaw, Justice Hall took a very narrow and technical approach by restricting ejusdem generis to situations where a list of specific terms is followed by a general term. This stands in sharp contrast to the modern interpretive approach he took with the Parks and Pathways Bylaw. If Justice Hall had taken such an approach with the Street Bylaw and had interpreted the words “any object or article” purposively and in context, it is likely that the ban on material in the street would have been seen as sufficiently intelligible rather than vague or overbroad. Analysis under s. 2(a) and (b) of the Charter would then have been required, and it is likely that Justice Hall would have found any intrusions of the Charter to be justifiable just as he did for the Parks and Pathways Bylaw (although perhaps the Street Bylaw’s lack of careful tailoring may have been an issue under the minimal impairment stage of Oakes). Regardless, it should not be difficult for the City to revise this bylaw to clarify that it is intended to apply to objects that frustrate the purpose of municipal streets.

For the most part Justice Hall’s analysis of freedom of religion is beyond challenge, although as noted above, he did not fully engage with Judge Fradsham’s finding that the City’s violation of s. 2(a) of the Charter was more than trivial or insubstantial. More seriously, Justice Hall stated in his reasons on freedom of religion that “a degree of deference is appropriate” (at para. 88), and attributed this statement to Chief Justice McLachlin in Hutterian Brethren. It must be noted, however, that the discussion of deference in Hutterian Brethren related to the Court’s approach under s.1 of the Charter. There is no authority which states that deference should be provided to government at the stage of interpreting constitutionally guaranteed rights and freedoms, and to the extent that Justice Hall’s decision suggests this approach, it is incorrect.

I also generally agree with Justice Hall’s reasons for decision under s. 1 of the Charter, but do have a couple of quibbles. Under the minimal impairment stage, Justice Hall did not provide much of his own analysis, and simply adopted the reasoning in several paragraphs of Montréal (City). One of my critiques of Judge Fradsham’s decision was that this leading case was not considered, and so it is positive to see the reliance on Montréal (City) on appeal. However, Justice Hall did not engage with the point made in Montréal (City) that because permits were available for sound projected outside, the ban on this form of sound was partial rather than absolute and therefore minimally impairing. While Judge Fradsham did not cite Montréal (City), he considered the lack of availability of permits to Pawlowski to be a challenge for the City under the minimal impairment stage. We are not told what impact, if any, the City’s blanket denial of permits to Pawlowski had on Justice Hall’s minimal impairment reasons.

Similarly, at the third and final proportionality stage of the Oakes test (as modified by Dagenais v. Canadian Broadcasting Corp., [1994] 3 S.C.R. 835), the focus is to be on whether the beneficial effects of the government action outweigh the negative effects on the Charter claimant’s rights. Justice Hall’s reasons focus almost entirely on the benefits of the law, with little attention to the impact of the ban on amplification on Pawlowski’s freedom of expression. Perhaps the problem here is similar to that which occurred in Hutterian Brethren, where the concession of a breach of freedom of religion meant that there was little evidence of the impact of that breach when it came time to weigh the negative versus positive effects of the law (for a comment on this aspect of Hutterian Brethren, see Jennifer Koshan and Jonnette Watson Hamilton, “‘Terrorism or Whatever’: The Implications of Alberta v. Hutterian Brethren of Wilson Colony for Women’s Equality and Social Justice” in Sheila McIntyre and Sanda Rodgers, eds., The Supreme Court of Canada and Social Justice: Commitment, Retrenchment or Retreat. (Markham, ON: LexisNexis Canada Inc., 2010) 221 at 229-230). It is questionable whether this oversight would have had an impact on the outcome under s.1, as the ban on amplification was arguably not a serious breach of Pawlowski’s freedom of expression – he was only banned from using a particular method of expression, sound amplification, and only in city parks. However, if the third proportionality stage under s.1 of the Charter is to have the new focus that the Supreme Court suggested in Hutterian Brethren, sufficient attention must be paid to the law’s impact on the rights of the Charter claimant at this stage.

Thanks to Jonnette Watson Hamilton for comments on an earlier version of this post.