Religious wing nuts, I thought

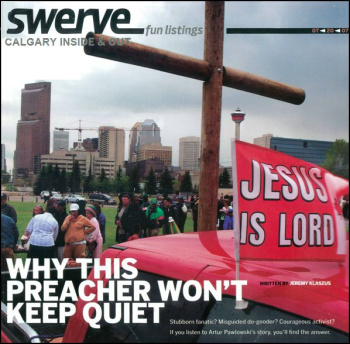

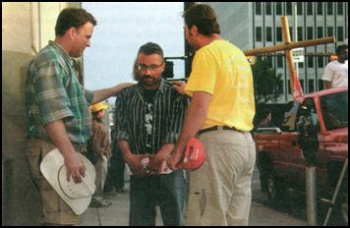

It was January, and a thin blanket of snow layered the city’s icy downtown. A group known simply as Street Church was meeting across from the Drop-In Centre in Triangle Park, a miserable stretch of ground pockmarked with gopher holes and often littered with needles. The church was making lots of noise. Mu-sic blared from a speaker system rigged to a red Dodge Ram pickup truck, and several people in the park danced to the music, enthusiastically waving giant coloured flags. On the back of the truck, a brown-haired man was shouting his message into a microphone in a Polish accent "God loves you," he said, his words spilling out onto the street and beyond. I had just encountered Calgary’s loudest preacher, Artur Pawlowski, who would make news headlines by fighting with the city about where and how loudly he could preach. Soon, the whole city would hear about this 34-year-old Polish immigrant-or at least about the loud speaker through which he spreads his gospel.

Being a recovered fundamentalist, I could recognize the "praise and worship" music playing over the speaker system: kitschy songs in minor keys about Jesus that made me cringe. A bunch of white evangelical Christians wrote these songs in the ’80s, trying to make music like the Hebrews of old. I thought about how this small fundamentalist church was proselytizing to some of the most vulnerable people in the city. Sure, they were offering food, drink and warm clothing to the 50 or so people who were lined up, rubbing their hands together and stamping their feet to keep warm. But I knew that wasn’t the true reason this mobile church was there. Pawlowski and his followers were there to make converts, to fill the air with sermons people would be forced to listen to, whether they wanted to or not.

Being a recovered fundamentalist, I could recognize the "praise and worship" music playing over the speaker system: kitschy songs in minor keys about Jesus that made me cringe. A bunch of white evangelical Christians wrote these songs in the ’80s, trying to make music like the Hebrews of old. I thought about how this small fundamentalist church was proselytizing to some of the most vulnerable people in the city. Sure, they were offering food, drink and warm clothing to the 50 or so people who were lined up, rubbing their hands together and stamping their feet to keep warm. But I knew that wasn’t the true reason this mobile church was there. Pawlowski and his followers were there to make converts, to fill the air with sermons people would be forced to listen to, whether they wanted to or not.

I had played that game before and knew it well: go to people in difficult life situations, present them with a simplistic message of salvation and expect a miracle. People sure have to put up with a lot for a meal, I thought as I walked away that January evening, Pawlowski’s voice fading as I left.

I knew, though, that I couldn’t really walk away from the loudspeaker preacher and his unruly church. We had too much in common. I was raised on the fundamentalist Christianity Pawlowski preaches. I went to a private Christian school and sang the pseudo-Hebrew kitsch songs every day, clapping at the right times to punctuate the rhythms. In the religious fervour of my youth, I wasn’t very different from Pawlowski. I, too, had earnestly wanted to save people from the everlasting torment that awaited them at life’s end. But age and time tempered my evangelicalism, and now it annoys me whenever I see anyone filled with the same fervour I once had. In Pawlowski, all I saw was a fanatic.

But because of what we had in common, I felt compelled to find out where his fanaticism came from. Who is Artur Pawlowski, really? An activist who’s standing up for those who have diminished voices in our city? Or a misguided do-gooder with an unrealistic mission to save Calgary’s poor? He’s a good showman, and I wanted to know the man behind the theatrics. As much as I didn’t want to admit it, I was drawn to this feisty Polish preacher who offered salvation along with a sandwich.

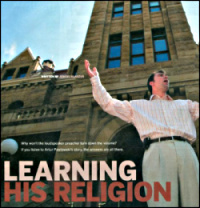

The preacher lives in a Shaganappi bungalow with his wife and two sons, Nathaniel, 7, and Gabriel, 2. You couldn’t miss his house if you wanted to. Every vehicle parked outside on the street is adorned with red Flames-style Jesus is Lord" flags specially ordered from communist China. I’m sitting on the couch in the living room. On the mantle sits a replica of the Ten Commandments. Looking out the window, I can see the Jesus flags on Pawlowski’s pickup truck, a vehicle he once used to build homes in the city. Over the past three months, I’ve spent hours here getting to know Artur and his family. He talks a lot, which means I listen a lot I’ve come with my reservations front and centre, but our conversations are showing me that all human beings, even headstrong fundamentalist preachers, are more complex than our judgments allow.

The preacher lives in a Shaganappi bungalow with his wife and two sons, Nathaniel, 7, and Gabriel, 2. You couldn’t miss his house if you wanted to. Every vehicle parked outside on the street is adorned with red Flames-style Jesus is Lord" flags specially ordered from communist China. I’m sitting on the couch in the living room. On the mantle sits a replica of the Ten Commandments. Looking out the window, I can see the Jesus flags on Pawlowski’s pickup truck, a vehicle he once used to build homes in the city. Over the past three months, I’ve spent hours here getting to know Artur and his family. He talks a lot, which means I listen a lot I’ve come with my reservations front and centre, but our conversations are showing me that all human beings, even headstrong fundamentalist preachers, are more complex than our judgments allow.

Here is the story he told me. Artur was born in Communist Poland in 1973, the eldest of two sons. His father was a coal-mine engineer and his mother ran a restaurant. During his formative years, Artur saw plenty of human-rights abuses. "I have seen tanks on the streets," he says. "[Ibe communist government] terrorized the press, and they terrorized citizens so they could keep them under subjection. And every time someone was raising up and saying this is illegal-what you’re doing is against humanity-they were thrown in jail."

The Communist Party lost its grip on Poland in 1989, but it would take the country years to recover. In 1990, the Pawlowski family fled Poland, taking only what they could carry on their backs. They settled in a village about 50 kilometres from Athens, Greece, where they lived for the next five and a half years. "We were building up from scratch over there," Artur says. In Greece, the then 17 – year old and his father became property developers. "I was making lots of money," Artur says. "I worked for the billionaires, the richest people on the planet. I built their summer houses in Athens."

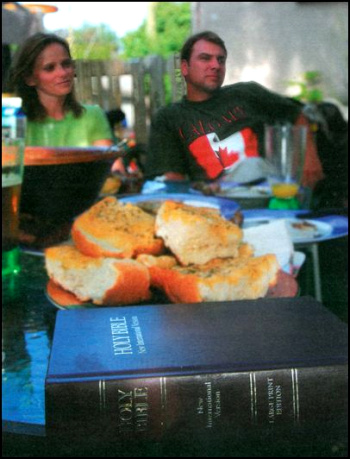

In 1992, Artur met his future wife, a beautiful 19-year -old Polish actress named Marzena who had immigrated to Greece a year earlier. She had recently converted to Christianity, but Artur didn’t think much of her new faith, which his bride-to-be found disturbing. "He was a very proud man," Marzena says. "He believed in God but he was far, far from him. He didn’t go to church because he didn’t like the system." Finally, she brought Artur to a Pentecostal church in Athens where a particular preacher was able to get past his distrust of authority. "I thought the church was to get your money. But then this guy was totally different," Artur says. "He preached love. No politics. No strings attached. No money. He didn’t care if you’re poor or rich. He was just saying that there’s someone who loves you regardless of what you did."

Once Artur became a Christian, he and Marzena weren’t expecting huge changes in their lives. "Because Artur has such a talent for making money, we always thought then we will be blessed, we will be very rich," she says. Sure enough, impressed by the Pawlowski’s business success, the Canadian consulate in Greece approached the family and asked them to consider moving to Canada. After some deliberation, the Pawlowski’s-Artur, his parents and his younger brother Dawid-immigrated in 1995, choosing Calgary on the advice of a friend living in the city. A year and a half later, Marzena was legally allowed to follow and the pair was married in 1997.

Once Artur became a Christian, he and Marzena weren’t expecting huge changes in their lives. "Because Artur has such a talent for making money, we always thought then we will be blessed, we will be very rich," she says. Sure enough, impressed by the Pawlowski’s business success, the Canadian consulate in Greece approached the family and asked them to consider moving to Canada. After some deliberation, the Pawlowski’s-Artur, his parents and his younger brother Dawid-immigrated in 1995, choosing Calgary on the advice of a friend living in the city. A year and a half later, Marzena was legally allowed to follow and the pair was married in 1997.

Artur and Marzena were, in many ways, a typical young Calgary couple: they saw plenty of opportunity in the city and worked hard. Soon after she arrived, Marzena urged Artur to get back into the construction business. He started Alberta General Contracting Corp. and Homes by Art, building houses in suburban communities like Shawnessy, Springbank and Bearspaw, employing up to 30 people and making up to $5,000 a day. The Pawlowski’s were materially blessed.

Then everything changed. In 2000, their first son, Nathaniel, was born with a diaphragmatic hernia, an abnormality of the diaphragm that is often fatal. "Basically what happened is he was born with his bowels on his lungs," says Marzena. "Suddenly it wasn’t about praying for blessing or this or that new toy in life. Suddenly it was about someone you love."

Then everything changed. In 2000, their first son, Nathaniel, was born with a diaphragmatic hernia, an abnormality of the diaphragm that is often fatal. "Basically what happened is he was born with his bowels on his lungs," says Marzena. "Suddenly it wasn’t about praying for blessing or this or that new toy in life. Suddenly it was about someone you love."

The experience made Artur re-evaluate his life. "It shook me to the point where I was willing to listen and let go of my ambitions," he says. Artur pleaded with God to heal his son. "I prayed: ‘Lord, if you spare my son, I will serve you for the rest of my life.’" His prayer was answered. Nathaniel had one operation, and recovered speedily. His parents say it’s a miracle. "He swims like a frog and runs and jumps," says Artur of his blond-haired son.

Compelled to follow through on his promise to God, Artur needed a mission.

The man who made his money building vacation homes for billionaires in Greece and luxury homes for upper-class families in Calgary began to pay attention to a part of society he hadn’t really considered before: people living on the street. "It disgusted me, the lifestyle of the rich, because we never even talked about the poor," he says. "They were like from another planet. And when I encountered the poor, it disgusted me so much that some people have so much money, and yet they choose not to do anything with poverty."

Artur joined up with a small ministry that was evangelizing on 17th Avenue every Monday night. He soon realized he had a choice. "I said, ‘Do I want to die a rich, pitiful and selfish man? Or do I want to live and make a difference?" He opted for the latter and, in 2004, abandoned his businesses to start Street Church with two other men from the ministry, Lawrence Irwin and Daniel Howard.

Artur joined up with a small ministry that was evangelizing on 17th Avenue every Monday night. He soon realized he had a choice. "I said, ‘Do I want to die a rich, pitiful and selfish man? Or do I want to live and make a difference?" He opted for the latter and, in 2004, abandoned his businesses to start Street Church with two other men from the ministry, Lawrence Irwin and Daniel Howard.

As politicians tried to figure out how to tackle the growing homelessness crisis in Calgary, Artur and his young friends jumped right in. Artur and Marzena gave $105,000 of their own money to get the ministry started at Triangle Park, often called Needle Park. "Church under the biggest roof in the world," Street Church likes to say. They were in for a rough ride. "You have to be bold in your character even to preach to those people," says Marzena, recalling the early days when Art was finding his preaching voice. "I remember when we started Street Church, they were trying to break his character from different angles. In the beginning, it was quite dangerous. It was, ‘Get out of here.’ But they started to come and cry. It takes character to be over there. Not everybody can do it."

Artur’s parents were also sceptical of their son’s new endeavour. "They said, ‘Why are you doing this? It doesn’t make sense," says Artur. "You’re good at business. Go back to working. Think of your kids."

Three years later, much has changed. Street Church has its own weekly TV show on the Lethbridge-based Miracle Channel. Artur has his parents’ approval. The people he is trying to reach listen. And the church is now entirely supported by donations, from which the couple is paid $2,000 a month-their sole source of income. "At the right time a man or woman will come forward with a cheque and say, ‘This is for the ministry,’ " says Artur, who says the church received more than $200,000 in donations last year.

Three years later, much has changed. Street Church has its own weekly TV show on the Lethbridge-based Miracle Channel. Artur has his parents’ approval. The people he is trying to reach listen. And the church is now entirely supported by donations, from which the couple is paid $2,000 a month-their sole source of income. "At the right time a man or woman will come forward with a cheque and say, ‘This is for the ministry,’ " says Artur, who says the church received more than $200,000 in donations last year.

Street Church also works with the Victorfy Outreach Centre to get people off the street and into transitional housing. (Victory has several transitional housing units in Forest Lawn and a 50-unit apartment in Ogden.) The partnership is somewhat surprising, as Artur is extremely sceptical of both the non-religious and religious organizations-particularly the shelters-in the city that work with the homeless. "They are maintaining the problem," he claims, although many would disagree. "We are addressing the problem. We are not having a great amount of money and huge buildings, but what we have is houses, a transitional housing project, and our love and our hands and our mouths saying ‘You don’t have to die.’ " The preacher is plainly pleased with himself and his ministry. He says Street Church served 55,000 meals last year and has helped get about f400 people off the street since 2004.

Regardless of how accurate those numbers may be (they’re impossible to verify), Artur has thrown himself fully into his very public calling. "For every hour that you see him out there, there’s 10 hours of work in the background that he does himself," says Luba Arko, 63, a long-time friend of the Pawlowski’s. The church currently meets east of the Drop-In Centre, between the C-Train tracks and the old Simmons building, on Sunday afternoons. Monday nights, they meet at various downtown locations. Wednesdays they meet at city hall around noon, much to the chagrin of bylaw officers. Wednesday night is a Bible study. Friday nights, they meet again near the Simmons building. And on Saturday evenings, the Pawlowski’s have a prayer time at their home. "I don’t know how many people would open their homes for the homeless, but my house is open," says Artur. (The Pawlowski’s own two houses in addition to their home. One is used for emergencies when someone needs a place to stay, and for Street Church storage. Artur’s brother Dawid lives in the other house with a roommate.)

After Saturday night prayer time, it starts all over again with the Sunday service at Triangle Park at 2 p.m. Everyone in the area knows they can count on Street Church to show up. "It don’t matter if it’s raining or not," says Barry Coles, a 45-year-old Newfoundlander who’s currently staying in the Drop-In Centre. "They’re coming, every Sunday."

This is what it’s like at a Sunday Street Church gathering: Artur stands on his pickup truck, preaching behind a red podium adorned with a white cross. A Canadian flag is strapped to the wooden cross standing on the back of his truck. Volunteers of varying ages serve hamburgers, hot dogs and vegetables to anyone who wants something to eat.

This is what it’s like at a Sunday Street Church gathering: Artur stands on his pickup truck, preaching behind a red podium adorned with a white cross. A Canadian flag is strapped to the wooden cross standing on the back of his truck. Volunteers of varying ages serve hamburgers, hot dogs and vegetables to anyone who wants something to eat.

People line up, one after another, for three solid hours. The church says it serves between 200 and 300 meals every time it’s in the park, and people in the line repeatedly tell me that the quality of the food far surpasses what’s served at the Drop-In Centre. Many of them work in construction, and are also given food for their lunches the next day. Everybody looks like they’re enjoying themselves, even as Artur shouts that only fools deny the existence of God. "These people aren’t hurting nobody, I’ll tell you that," says Coles as he finishes his meal. "They’re helping. In the winter there’d be more people dead if it wasn’t for these people."

Behind the food line, a few children-including the Pawlowski’s son Nathaniel-kick around a soccer ball. "Kids change the atmosphere," says Marzena, recalling a conversation she had with a homeless man last summer. "He was amazed that anyone would bring their children to one of the most dangerous areas of the city. The man was overwhelmed. This is the thing," she continues, ”when you treat homeless people like animals, they act like animals. But when you come and treat them like normal human beings, they are normal human beings."

For over two years, the Street Church gathered without trouble at Triangle Park. But last year, noise complaints started pouring into the city because of the church’s amplified music and preaching. Bylaw officers investigated the com-plaints, and found repeatedly that the church hadn’t exceeded the acceptable limit of 75 decibels, the noise level of a small air compressor. Art bought a noise meter, and found he registered between 65 and 70 decibels with his amplification-the noise level of normal conversation when you’re standing about three feet away from someone. Nevertheless, in January the city forbade the church from using any amplified sound in Triangle Park. Artur refused to accept this, and continued using his speakers. "The government wanted to take the very tool that makes this ministry successful," he says. In April, the city revoked Street Church’s parks permit altogether. The church is currently suing the city over the crackdown, alleging the city is violating the church’s constitutional rights.

Then came the fines. Since January, Artur and other members of Street Church have been hit with more than 20 police and bylaw tickets for a wide array of alleged offenses, including causing objectionable noise, causing unnecessary noise from a motor vehicle, jaywalking, stunting, placing material on a street, offering goods and services on a street and offering goods and services in a park. These last two especially infuriate Artur. "So every time you give a cup of water to someone who’s thirsty, it’s illegal," he says. "Think about it, If there is a starving kid in that park, I’m not allowed to go there and feed that kid. That kid will have to die … Drug dealers are there. Prostitutes are there. But [police and bylaw officers] don’t go after them-they go after us."

Then came the fines. Since January, Artur and other members of Street Church have been hit with more than 20 police and bylaw tickets for a wide array of alleged offenses, including causing objectionable noise, causing unnecessary noise from a motor vehicle, jaywalking, stunting, placing material on a street, offering goods and services on a street and offering goods and services in a park. These last two especially infuriate Artur. "So every time you give a cup of water to someone who’s thirsty, it’s illegal," he says. "Think about it, If there is a starving kid in that park, I’m not allowed to go there and feed that kid. That kid will have to die … Drug dealers are there. Prostitutes are there. But [police and bylaw officers] don’t go after them-they go after us."

Street Church has racked up more than $2,000 in fines – "Giving tickets for feeding the poor. It’s just ridiculous," says Artur. The church also had one of its signs confiscated by police in June. The city would not comment on the specifics of the bylaw tickets. "[Bylaw officers] are not trying to do anything untoward," says Roger Matas, a city spokesperson. "Certainly if there was no reason to issue a ticket, a ticket would not have been issued … Enforcement is the last resort "

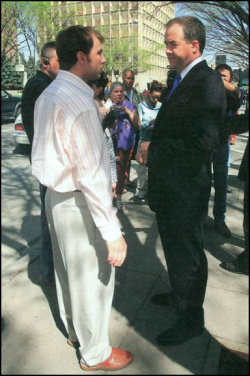

This ongoing dispute with the city makes for good headlines and TV, and Artur is quick to cast himself as a martyr and the city as a harsh oppressor. After the church’ s Triangle Park permit got revoked, it started meeting right in front of Old City Hall on Wednesdays. "If we can’t be feeding the poor where we should be, we’ll feed them right outside your window," Artur says. It makes for a good media spectacle, especially when the mayor shows up.

And show up he did on a Wednesday in mid-May. Dave Bronconnier casually exited Old City Hall and found Street Church-signs, banners, homeless people, volunteers and, of course, Artur-spread out on the sidewalk in front of him. Artur seized on the opportunity, rallying the television cameras and confronting Bronconnier. "Are you going to continue to ignore the rights of the homeless?" he shouted. "Our rights?" The two men had a short conversation in which the mayor urged Artur to "drop the rhetoric and deal with the issues." When Artur kept demanding the city respect the rights of homeless people and his church, the mayor finally walked away. "You see, the mayor just doesn’t want to get the picture that we’re not breaking any noise violation," the preacher said to his audience of reporters. It was completely in character, and while I saw the arrogance of his stance, I also recognized his courage. After so much watching, so much listening, had I begun to admire his refusal to shut up?

City officials don’t like Artur because he’s loud. People across the river in Bridgeland don’t like Artur because he’s loud. Artur, however, is completely unfazed by all this, and the city’s attempts to quiet him down only serve to fire him up more. Ever hyperbolic, he angrily knocks his index finger atop the stack of bylaw tickets on his coffee table. "Fifty thousand communists in Poland ruled over 40 million Polish people," Artur says. "A small group of people terrified the whole nation, by fear, by this kind of approach. My father could not enter a church building because he would lose his job. Now his son is deprived of exactly the same rights in a country that he thought his son would be free."

City officials don’t like Artur because he’s loud. People across the river in Bridgeland don’t like Artur because he’s loud. Artur, however, is completely unfazed by all this, and the city’s attempts to quiet him down only serve to fire him up more. Ever hyperbolic, he angrily knocks his index finger atop the stack of bylaw tickets on his coffee table. "Fifty thousand communists in Poland ruled over 40 million Polish people," Artur says. "A small group of people terrified the whole nation, by fear, by this kind of approach. My father could not enter a church building because he would lose his job. Now his son is deprived of exactly the same rights in a country that he thought his son would be free."

Let me be dear: Artur is stubborn as hell, the Pawlowski’s are unflinchingly fundamentalist and their ideas are jarring to modern sensibilities. Artur calls the theory of evolution "pathetic, ridiculous and stupid." Marzena tells me homosexuality is "sick." The Pawlowski’s send Nathaniel to a private Christian school. "We value life. In the public schools, they don’t," Artur says. "[In public schools], they are teaching them we came from monkeys. No, my grandfather is not in a zoo. I don’t want my kids to be twisted by someone’s views."

As someone who grew up being taught that homosexuality is an abomination and evolution is a conspiracy of God-hating baby-eating probably-gay secular humanists, I can’t help but shudder. But after months of listening to Artur, I’ve realized that even though he can be frustratingly dogmatic, he’s not the fanatic I thought he was. He’s a man who gave up a successful business to do work few people in this city would do. True, he’s chosen to do it his way-on the street and with an amplifier. But consider the alternatives. "What do you prefer?" asks Artur. "Drug dealing, prostitutes and killing? Or music for a few hours and a bunch of volunteers keeping peace in the area?"

At Street Church, I was sure I’d find someone in the food line eager to stuff a sock in Artur’s mouth, or at least have him turn down the volume. No one seemed to have a problem with him, though. "They helped me when I needed it," says 21 year-old Vanessa Loyer, one of Artur’s converts. "They fed my son when I didn’t know where I’d get baby food." One after the other they told me they appreciated the church’s presence downtown, even if they weren’t completely sold on its religious message. "All they’re saying is do something better with your life," says Terry Donovan, 36, motioning towards the volunteers dishing out food. "You go through this line and look at each of these people. There’s six sets of eyes there, and each of them looks at you as if you’re just as good as them." He adds sarcastically: "Aren’t these the evilest bunch of bastards you’ve ever seen? Somebody call the cops on these people."

However, there was one person who didn’t want to hear Art’s message: his brother Dawid, now 28. After the Pawlowski’s immigrated to Calgary, Dawid got involved in a gang and became addicted to drugs and alcohol. His life deteriorated, even as Artur became more successful. "I was stealing from my brother," Dawid says. "I was stealing from anywhere I could just to get a fix … I was a horrible, horrible brother." When Artur would preach in Triangle Park, Dawid would see him from "crack cul-de-sac" where he was smoking crack and picking up prostitutes. He could hear Artur talking about a God of love, and Dawid would angrily flash his middle finger at his brother. "I wanted what he had-the freedom-but I hated him, because he had something I craved: not to be a slave," says Dawid.

However, there was one person who didn’t want to hear Art’s message: his brother Dawid, now 28. After the Pawlowski’s immigrated to Calgary, Dawid got involved in a gang and became addicted to drugs and alcohol. His life deteriorated, even as Artur became more successful. "I was stealing from my brother," Dawid says. "I was stealing from anywhere I could just to get a fix … I was a horrible, horrible brother." When Artur would preach in Triangle Park, Dawid would see him from "crack cul-de-sac" where he was smoking crack and picking up prostitutes. He could hear Artur talking about a God of love, and Dawid would angrily flash his middle finger at his brother. "I wanted what he had-the freedom-but I hated him, because he had something I craved: not to be a slave," says Dawid.

But Artur, ever the stubborn one, wouldn’t let Dawid go. After all, Artur hardly came to faith easily. It took years for Marzena to persuade him to go to church. After that, it took the near-death of his son for him to really put his faith into practice. Having played the part of the reluctant convert himself, Artur wasn’t about to give up on his brother. It paid off. About a year and a half ago Dawid fell to his knees and "screamed on the name of the Lord," as he puts it He joined the church. He gave up his demons. And now, Dawid is starting to preach too, sharing his story with others who are stuck in his old addictions.

Just like his older brother, Dawid uses the loudspeaker when he preaches. And like Artur, Dawid doesn’t care if he upsets someone. "Praise the Lord," he says. "If they called Jesus Christ a drunkard … how much more do we deserve?" Dawid is still finding his voice, but he has a role model who continues to gently guide him. "Artur never gave up on me. I would steal from him. I would lie to him. But he never gave up," says Dawid. "He always preached the message of hope."