Four Little Girls and the Fight For Freedom

Four Little Girls and the Fight For Freedom

The Birmingham Bombing of 1963

This city earned the nickname “Bombingham” after many attacks by racists during the struggles of the 1960s. Here is the story of the struggles and the infamous church bombing of Birmingham 1963–a story that has also been recently documented in Spike Lee’s powerful film Four Little Girls.

It was 1963. One hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of slavery, Birmingham was still a stronghold of racism and Jim Crow segregation. The city was a modern industrial powerhouse of coal and steel. It was run on behalf of the largest monopoly corporations by a hateful, narrow-minded white-racist powerstructure. Thirty-eight percent of the population was Black–living under infuriating conditions of discrimination and poverty.

In the downtown department stores, Black people were free to buy whatever their paychecks could afford–but they were forbidden to use the restrooms, or order a grilled cheese at the lunch counters, or get a job behind one of the cash registers. Signs everywhere said “Whites Only.”

In Birmingham, like in most of the South, many white people still insultingly called adult Black people by their first names–and Black men were often casually called “boy.” Schools were segregated –and the education for Black children was starkly inferior and underfunded.

This unjust setup was enforced by a brutal and racist police department and by the Ku Klux Klan movement, the semi-official terror arm of the powerstructure. Birmingham was already known for nighttime bombing attacks on the Black community by white supremacists.

Birmingham had been like this for a long time, and many people thought it would never change. But this was 1963, and Black people were starting to feel deeply that time was up–been up!–for the structure and tradition of white supremacy. All across the South, and increasingly in the North, different organizing projects were mobilizing people to challenge and defy the system. And they would be met with all the brutality and deception that this system could muster.

Fighting the Pharaohs

of Birmingham

How many years must a people exist,

before they’re allowed to be free?

The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind,

The answer is blowing in the wind.

Bob Dylan’s song, sung by Peter, Paul and Mary,

bumped “Puppy Love” at the top of the charts,

March 1963

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) decided Birmingham would be their battlefield. This was a time of intense debate within the Civil Rights Movement and SCLC was being challenged by more militant tactics and strategies proposed by the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

SCLC’s plan was to showcase their approach in Birmingham by organizing economic boycotts of downtown businesses and nonviolent protest marches. They called this “Project C” for confrontation.

SCLC was based in the Black churches of the South. In Birmingham SCLC set up its organizing center in the yellow-brick Sixteenth Street Baptist Church–on the edge of Kelly Ingram Park, right in the middle of Birmingham’s Black business district. The leaders of the campaign stayed at the Black-owned Gaston Motel.

Starting on April 3, 1963, small squads of activists would leave the church and head for the downtown shopping district–picketing with signs, taking their seats at the “whites only” lunch counters and demanding to be served. In the beginning their numbers were very small. But hundreds of Black people started to gather in the park and along the streets to downtown–to watch, to shout support, to decide in their own minds whether to join up and risk everything.

The local police department considered this movement dangerous and illegal. The FBI had just orchestrated a national media campaign charging that the civil rights movement was “communist-inspired”–saying that the organized challenge to white supremacy was threatening the whole social order of the U.S.

The city’s police commissioner, Bull Connors, announced that he would mass cops within sight of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and simply arrest everyone who tried to march downtown. On the first mass march to downtown, April 6, all 50 people were jailed. The next day, the crowd grew to 600, and the police attacked viciously.

Day after day, marchers would leave the church to confront the police and try to march. Night after night, the activists met for training workshops and mass meetings.

The police department used clubs, K-9 dogs and the waterhoses of the fire department. They bragged that the city’s new firehoses could rip bricks from a wall and skin bark off a tree. They would drench the marchers and the crowds of onlookers–and then focus tight water spray on the front ranks.

A local judge issued an injunction making any marches illegal–and giving the police the authority to arrest anyone who headed downtown. In the Alabama state capitol, the governor George Wallace rushed to write a new law that raised appeal bonds for misdemeanors from $300 to $2,500–but only in Birmingham. They intended to sweep the protesters into jail, and bankrupt the movement.

On April 12, 50 people left the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church to defy the injunction. People lined the streets to watch. All 50 were arrested, including Reverend King who was thrown into solitary confinement.

By May 1, after a month of repeated confrontations, 1,000 people were in jail or on bond. The mood was heavy–the police and the powerstructure seemed ruthless in their determination, and the organizers feared they may be facing a stalemate.

Freedom NOW!

At that point a powerful, unexpected force stepped forward. The movement took root among the city’s Black youth. Larger and larger numbers of kids had been skipping school and showing up at the organizing meetings. It started with the high school students–but soon there were kids from the grade schools too, demanding to be allowed to march. Some in the leadership believed that no one under 18 should be allowed to face the police. But the kids themselves were determined, and they were needed.

FBI spies told the Birmingham police that leaflets in the Black high schools called for a walkout at noon on the coming Thursday. “Tall Paul,” the popular local disk jockey, started announcing a “big party” Thursday at Kelly Ingram Park. And everyone knew what that meant.

The debate among the youth was intense. Many were forbidden by their parents to get involved. Many were told that getting arrested would ruin their lives, and that they should focus on getting an education. Some were told that the student activists were a “low class” of people–troublemakers led by outsiders.

The slogan of the student organizers was “Fight for freedom first, then go to school!”

Thursday, May 2, was a hot, muggy day. Everyone around the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church could hear the singing of those inside. At 1 o’clock, the first 50 youth came marching out in pairs–singing, dancing, jubilant. One observer said the anthem “We Shall Overcome” lost its slow, spiritual feel–their voices carried a fighting spirit. At least 1,000 youth gathered to face the cops. Many had lied to their parents.

One police captain told how he tried to intimidate a group of 40 elementary school kids into going home. They stood their ground and told him straight–they knew what they were doing and would not back down.

As the kids marched forward from the church, the firemen aimed the hoses of three firetrucks at the crowd and opened up. The front line wavered. Many were blasted backward down the street. A voice cried out, “Sing, children, sing!” And the crowd pressed forward into the spray.

The cops waded in with snarling dogs. The crowd shouted in rage. Some ran away. And the cops pushed forward, singling out those who stood their ground, ordering their dogs to bite. Still the youth held their ground. Crowds of seven and eight-year-old girls faced the cops, chanting “Freedom! Freedom NOW!”

The police started hauling off the kids. They filled paddy wagons and squad cars, while the youth kept pressing forward, looking for a hole in the police lines, looking for a way to go downtown. In the end the police had to bring up school buses. Six hundred children and teenagers were hauled off to jail. Three teenagers were hospitalized from dogbites, while an unknown number were treated in people’s homes.

The local press denounced the movement for allowing children onto the frontlines. But, by the next day, the whole world had seen the hateful face of Bull Connors, and knew from TV and newspapers that in the United States police dogs were used to attack Black children.

The next day, the youth were back again. Many stepped forward to replace those arrested or hurt. Again a thousand youth faced the firehoses and police dogs. The water blasted at 60 in the first ranks, and 50 were washed away–some even getting wedged underneath parked cars. Ten managed to hold their ground, soaked and singing the word “Freedom” to the tune of the hymn Amen. The firemen concentrated their hoses on them–as more people pressed forward. The crowd sat down on the street to stabilize themselves and would not move.

One man looked out of his nearby office window and saw a small Black girl literally tumbled down the street in blasts of water. Ashamed, he swore he would not be a bystander anymore.

Some among the youth broke with the leading doctrine of nonviolence. They took up rocks against the firemen and police. Their counterattack stunned and pinned down the authorities long enough for a large part of the youth to break through the encirclement and make it downtown.

On Monday, May 6, the youth did it again. By the end of that day, there were over 2,000 demonstrators in jail. The masses themselves were now deeply committed. Police now faced rocks and bottles when they dared patrol the Black communities. Adults stepped forward to support the youth, and some of them reportedly came to the rallies armed with guns. Meanwhile, the struggle in Birmingham had won worldwide attention, and supporters were arriving from all over the country to stand with the heroic youth.

There was intense worry at the highest levels of the U.S. government. The White House sent a representative to Birmingham to meet with the local ruling class. Representatives of the major monopoly corporations in town–Ford, Royal Crown Cola, and U.S. Steel–had a semi-official ruling council with local bankers and merchants called the “Big Mules” (officially listed as the “Senior Citizens Committee”). Seventy of the “Big Mules” met in downtown Birmingham to decide what to do. Their initial plan was to call for martial law, bring in troops, and start shooting the people if necessary. While they discussed this plan, 600 highly organized pickets suddenly appeared in the heart of the business district, stopping traffic and business as usual. One estimate said that 3,000 people were involved in running engagements with the cops throughout the city. It suddenly occurred to these “Big Mules” that even troops might not be able to enforce their old order for long. They took the White House advice and decided to grant concessions–though the idea of negotiating with Black protest leaders made them furious.

Two days later, after secret negotiations, it was announced that there would be desegregation of lunch counters, restrooms, department store fitting rooms and drinking fountains within 90 days. Arrangements were made to release all of those arrested. The struggle had forced a historic victory from the oppressors.

Attack and Counter-Attack

However, the battle of Birmingham was far from over. Powerful forces in the local powerstructure announced plans for a racist boycott of downtown stores to oppose integration–saying that white people should refuse to eat or try on clothes next to Black people. The Ku Klux Klan stepped out and held a rally on the outskirts of town on May 11. As the Kluckers saluted their flaming crosses, there were calls for action.

That night two bombs blasted the home of Reverend A.D. King, brother of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Less than an hour later, a bomb rocked the Gaston Motel. The racist forces had counterattacked by threatening the leaders of the movement.

As news spread, thousands of Black people took to the streets and drove the police out of the Black parts of town. Police cars were trashed, and several cops were injured. Late into the night, the shouts rang out “Freedom! Freedom NOW!” as flames rose 150 feet in the air.

The ruling class moved on many levels to contain this explosion of struggle. President Kennedy ordered federal troops to the outskirts of Birmingham–directly threatening the masses of people with armed suppression. At the same time, the system also offered new concessions to the people–a new Civil Rights Act started moving more rapidly through Congress that mandated equal rights in public accommodations (like rest rooms, motels, restaurants and drinking fountains) and gave the Attorney General more powers to sue states over nakedly discriminatory laws and practices.

Meanwhile, in June and July, new struggles broke out in cities across the U.S.–often copying techniques developed in Birmingham. In Mississippi, the racist assassins struck again. Medgar Evers, leader of the civil rights movement in Jackson, was murdered.

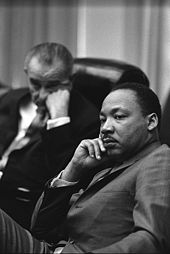

All during these months, the ruling class worked to strengthen its ties and influence within the civil rights movement itself. President Kennedy held meetings with various leaders within the movement–working to promote those leaders most loyal to the system, including Martin Luther King Jr. Plans were cooked up to use the August March on Washington to consolidate the mushrooming movement under a moderate program and tighter ruling class political control.

“Now, They’re Killing

Our Children!”

Meanwhile, back in Birmingham, Black people pressed on for an end to Jim Crow segregation, and the reactionary powerstructure fought hard to maintain their traditional system. Five Black students were scheduled to enter formerly white schools that September. Birmingham’s mayor (who was called a “reformer”!) asked a federal court to postpone the action and consider so-called “evidence of inherent differences in the races.”

Another bombing hit the home of an activist, touching off another long night of resistance. By now the police had a riot tank to send against the people. One Black person was killed.

Governor Wallace proposed that the schools scheduled for integration should simply be shut down. And when September 9 came, he sent national guard troops to prevent the Black kids from attending the schools. President Kennedy announced federal authority over the troops and withdrew them from Birmingham. The Black kids walked into the formerly white schools.

That Sunday, September 15, inside the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, four young girls had snuck out of bible class and were talking in the basement ladies room. They were dressed in white from head to toe because this was the church’s annual Youth Day and they had a special role in the 11 o’clock service. Suddenly a blast shook the building, and showered everyone inside with debris. The air filled with shouts, then moans, then sirens.

Maxine McNair searched desperately for her daughter. She found her father crying in the rubble. “She’s dead, baby,” he said, “I’ve got one of her shoes.” Looking at the horror on his daughter’s face made him yell out, “I’d like to blow this whole town up.” Ten-year-old Sarah Collins staggered out of the hole in the outer wall. She was partially blinded, and bleeding from her nose and ears. Twenty others had been injured and were taken to the University Hospital.

In the ruins of the church basement, the four girls in white were found dead: Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley, Addie Mae Collins and Carol Robertson–ages 11 to 14.

Eyes of the World

“On behalf of the Chinese people, I wish to take this opportunity to express our resolute support for the American Negroes in their struggle against racial discrimination and for freedom and equal rights… I am firmly convinced that, with the support of more than 90 percent of the people of the world, the American Negroes will be victorious in their struggle. The evil system of colonialism and imperialism arose and throve with the enslavement of Negroes and the trade in Negroes, and it will surely come to its end with the complete emancipation of the Black people.”

Mao Tsetung on the

Struggle Against Racial Discrimination

by U.S. Imperialism, 1963

The brutal bombing of the Birmingham movement’s headquarters was intended to terrify people–but it had the opposite effect. The sad news spread like a shockwave and electrified people. After seeing firehoses and police dogs, people all over the world now had even more proof of the heartlessness of those defending segregation.

With this bombing and the killing of the four girls, many people felt an intense connection with this struggle against injustice. Many decided that they could no longer hold back. Over the next year, many student volunteers–both Black and white–signed up with SNCC to take the message of the movement into the most repressive counties of Mississippi.

It was widely known in Birmingham who had done the bombing. Certainly it was known by the FBI who had close ties and operatives at all levels of the Klan. The bombing had been carried out by a team of white racists, including Robert Chamblis whose nickname was “Dynamite Bob.” But the powerstructure protected these men–as it always had. That too was a lesson for people watching the Birmingham events. Chamblis didn’t come to trial until 1977 and his accomplices were never tried.

Malcolm X, then a Muslim minister in Harlem, spoke of this in his speech “The Ballot or the Bullet”: “Any time you and I sit around and read where they bomb a church and murder in cold blood, not some grownups, but four little girls while they were praying to the same god the white man has taught them to pray to, and you and I see the government go down and can’t find out who did it. Why, this man–he can find Eichmann hiding down in Argentina somewhere. Let two or three American soldiers, who are minding somebody else’s business way over in south Vietnam, get killed, and he’ll send battleships, sticking his nose in their business.”

Malcolm X argued that “in areas where the government has proven itself either unwilling or unable to defend the lives and property of Negroes, it’s time for Negroes to defend themselves.”

This was a shocking message for many. It certainly ran directly counter to the direction the ruling class proposed for the civil rights movement. But Malcolm’s militant views reflected the hard experiences of the struggle. In Louisiana the “Deacons for Self Defense” were formed–to act as armed defense squads to the larger civil rights movement. In many other places in the country, activists started studying new philosophies and revolutionary ideologies.

Birmingham, Alabama 1963–the powerstructure tried to stop change. They used their police, their waterhoses and their dogs. When that didn’t work, they unleashed their hidden networks of racist bombers to kill four young girls in the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

History shows that the cowardly brutality of these men could not stop the just struggle of Black people–and it certainly could not dampen the militancy and visionary courage of the youth which then, in 1963, was just starting to show its power.

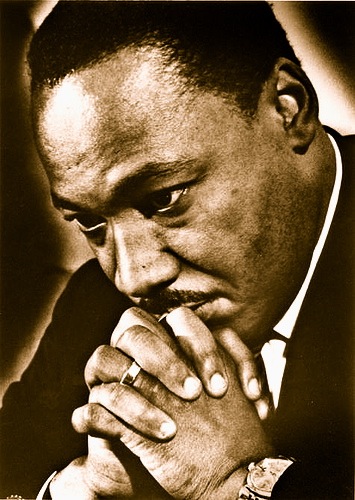

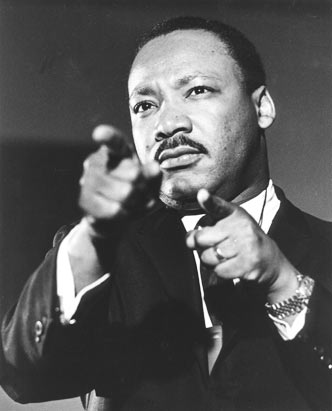

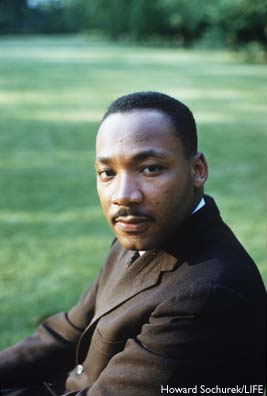

Martin Luther King, Jr., (January 15, 1929-April 4, 1968) was born Michael Luther King, Jr., but later had his name changed to Martin. His grandfather began the family’s long tenure as pastors of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, serving from 1914 to 1931; his father has served from then until the present, and from 1960 until his death Martin Luther acted as co-pastor. Martin Luther attended segregated public schools in Georgia, graduating from high school at the age of fifteen; he received the B. A. degree in 1948 from Morehouse College, a distinguished Negro institution of Atlanta from which both his father and grandfather had graduated. After three years of theological study at Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania where he was elected president of a predominantly white senior class, he was awarded the B.D. in 1951. With a fellowship won at Crozer, he enrolled in graduate studies at Boston University, completing his residence for the doctorate in 1953 and receiving the degree in 1955. In Boston he met and married Coretta Scott, a young woman of uncommon intellectual and artistic attainments. Two sons and two daughters were born into the family.

In 1954, Martin Luther King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Always a strong worker for civil rights for members of his race, King was, by this time, a member of the executive committee of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the leading organization of its kind in the nation. He was ready, then, early in December, 1955, to accept the leadership of the first great Negro nonviolent demonstration of contemporary times in the United States, the bus boycott described by Gunnar Jahn in his presentation speech in honor of the laureate. The boycott lasted 382 days. On December 21, 1956, after the Supreme Court of the United States had declared unconstitutional the laws requiring segregation on buses, Negroes and whites rode the buses as equals. During these days of boycott, King was arrested, his home was bombed, he was subjected to personal abuse, but at the same time he emerged as a Negro leader of the first rank.

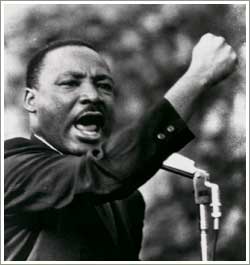

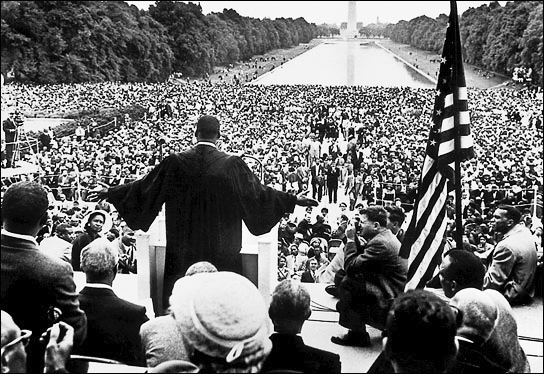

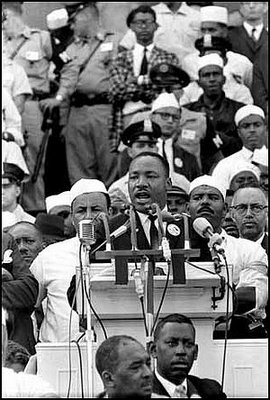

In 1957 he was elected president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization formed to provide new leadership for the now burgeoning civil rights movement. The ideals for this organization he took from Christianity; its operational techniques from Gandhi. In the eleven-year period between 1957 and 1968, King traveled over six million miles and spoke over twenty-five hundred times, appearing wherever there was injustice, protest, and action; and meanwhile he wrote five books as well as numerous articles. In these years, he led a massive protest in Birmingham, Alabama, that caught the attention of the entire world, providing what he called a coalition of conscience. and inspiring his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”, a manifesto of the Negro revolution; he planned the drives in Alabama for the registration of Negroes as voters; he directed the peaceful march on Washington, D.C., of 250,000 people to whom he delivered his address, “l Have a Dream”, he conferred with President John F. Kennedy and campaigned for President Lyndon B. Johnson; he was arrested upwards of twenty times and assaulted at least four times; he was awarded five honorary degrees; was named Man of the Year by Time magazine in 1963; and became not only the symbolic leader of American blacks but also a world figure.

At the age of thirty-five, Martin Luther King, Jr., was the youngest man to have received the Nobel Peace Prize. When notified of his selection, he announced that he would turn over the prize money of $54,123 to the furtherance of the civil rights movement.

On the evening of April 4, 1968, while standing on the balcony of his motel room in Memphis, Tennessee, where he was to lead a protest march in sympathy with striking garbage workers of that city, he was assassinated.

King was awarded at least fifty honorary degrees from colleges and universities in the U.S. and elsewhere. Besides winning the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, in 1965 King was awarded the American Liberties Medallion by the American Jewish Committee for his “exceptional advancement of the principles of human liberty”. Reverend King said in his acceptance remarks, “Freedom is one thing. You have it all or you are not free”. King was also awarded the Pacem in Terris Award, named after a 1963 encyclical letter by Pope John XXIII calling for all people to strive for peace. In 1966, the Planned Parenthood Federation of America awarded King the Margaret Sanger Award for “his courageous resistance to bigotry and his lifelong dedication to the advancement of social justice and human dignity.” King was posthumously awarded the Marcus Garvey Prize for Human Rights by Jamaica in 1968. In 1971, King was posthumously awarded the Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album for his Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam. Six years later, the Presidential Medal of Freedom was awarded to King by Jimmy Carter.King and his wife were also awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2004. King was second in Gallup’s List of Widely Admired People in the 20th century. In 1963 King was named Time Person of the Year and in 2000, King was voted sixth in the Person of the Century poll by the same magazine.King was elected third in the Greatest American contest conducted by the Discovery Channel and AOL. More than 730 cities in the United States have streets named after King. King County, Washington rededicated its name in his honor in 1986, and changed its logo to an image of his face in 2007. The city government center in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, is named in honor of King.King is remembered as a martyr by the Episcopal Church in the United States of America (feast day April 4) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (feast day January 15). In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Martin Luther King, Jr. on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

“I Have a Dream”

delivered 28 August 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington D.C.

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the “unalienable Rights” of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so, we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of Now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. And there will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people, who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice: In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.

The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.

We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead.

We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their self-hood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: “For Whites Only.” We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until “justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.”¹

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. And some of you have come from areas where your quest — quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of “interposition” and “nullification” — one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; “and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.”

This is our hope, and this is the faith that I go back to the South with.

With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day — this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning:

My country ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing.

Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim’s pride,

From every mountainside, let freedom ring!

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.

Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado.

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that:

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi.

From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual:

Free at last! Free at last!

Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!

“I Have a Dream” speech, given in front of the

Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.